Playlists

01-22-2022 • Ryan Prendergast

I've made hundreds of lists in my life, maybe thousands. It's my go-to thing to do. Have a problem? Make a list. Like something? Make a list of it and things like it.

I regularly run into a certain kind of problem, though. This came up a year ago, when I tried to make a list of books to read. I had enough books that I broke up the list into superlists: I had a nonfiction section, with list names like "Topic: history".

Here's a section.

- Nonfiction

- Topic: Physics and Math

- Elements of Mathematics: From Euclid to Gödel

- The Weil Conjectures: On Math and the Pursuit of the Unknown

- Bourbaki: A Secret Society of Mathematicians

- The Shape of a Life: One Mathematician's Search for the Universe's Hidden Geometry

- Physics from Finance: A gentle introduction to gauge theories, fundamental interactions and fiber bundles

- Structures: Or Why Things Don't Fall Down

- The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman (Helix Books)

- A History of Mathematics

- Misc

- Behavioral Psychology / Philosophy

- Topic: Physics and Math

This list is incredibly boring. It isn't very useful, because after I create it, I ignore it. It is a chore to make, and I never bother to add new books to it.

I run into the same problem making lists of movies, lists of websites, lists of ideas, lists of tasks, and any other kind. I find lists useful, but a chore to create and maintain. You might say "such is life, suck it up and do it even though it's a chore", but I refuse. A solution is only good as good as what actually happens, not the hypothetical best you could imagine it to be. So, can we make better lists?

Structuring a list

Lists collect a bunch of items: books, movies, etc. We want to balance being successful (something I'll actually make / maintain) with being useful (something I refer back to).

To be SUCCESSFUL, lists should be easy to add to. Creating a list is a matter of recall: I stream-of-conscious write out all the books I want to read that I remember right now. The easiest possible structure is a single long list of every book I think of.

To be USEFUL, lists need to recommend something. The process goes "Hm I want to read a book" —(check list)—> a particular book to read.

With too many items (~20), going through the list is nontrivial work, so the list is useless. That's when you decide to breakup a list into a superlist of lists, each list with a name.

Grouping Items

There's an extremely important moment when you turn a single long list into a hierarchy of superlists. You have to decide: by what mechanism will I separate books into different groups? This decision is usually done subconsciously. But subconscious defaults are still decisions!

The default subconscious decision is to group by category, by genre. I categorized my books by category. Nonfiction nests either into Math or Psychology, with a "Misc" block to take anything that doesn't fit well into a genre.

Group by category

Category lists are pretty okay at collecting a medium sized number of items (~20 – ~50).

But category lists really aren't that useful, because they fail at recall. Brains don't think in genres. I've never thought "Hm I'd like to read a behavioral psychology book", in the same way I don't think "oh let's listen to some Folktronica" with music.

Brain recall is illegibly associative. Most lookups I want to do are things like "oh I liked the whole NYC suits-doing-business of Power Broker, but I want something less dense". Genre lists are useless at doing that kind of search.

I also quickly run into tricky problems defining categories. I have German language books on my list. Do I put the German-language books in their own German section, and have a German-fiction German-nonfiction subsections, or do I intersperse German language books in the normal lists?

When grouping by category, each book should ideally exist in only one category, and categories should be exactly as specific to make that possible. This is why music genres get more specific by place and era: Polish alt-trance, eg. What if we remove that requirement?

Revealed preferences on Spotify

The best feature of Spotify is the centering of user-created playlists. These are public and like-able, so that popular ones spread.

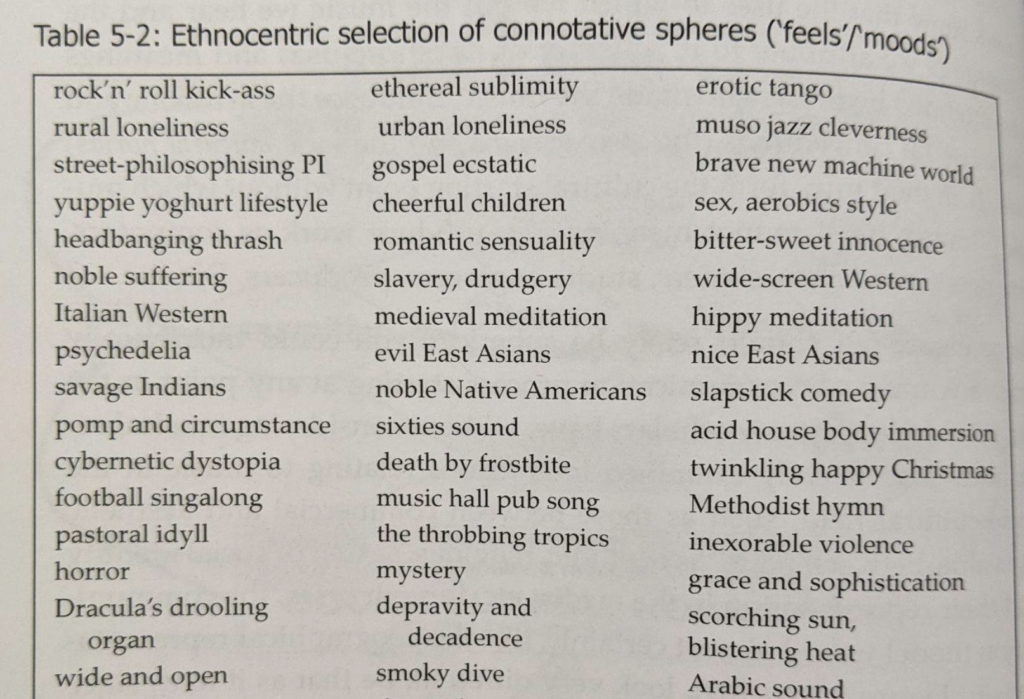

Spotify creates categorical playlists by genre, like "Grunge Forever" with some Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains. Users, however, overwhelmingly make playlists with names like "wonderfully chaotic", "just sitting in my room" "vaguely experimental: myspace lol 2008 xD" or "norwegian wood" What does it mean for a song to categorically sound like Myspace or a Murakami book? It doesn't mean anything clear, because it's not categorical. These are associative lists.

Associative lists are more useful than category lists, and they're easier to make. They don't need find every song that could fit in the list, only some. Associative lists are an emergent phenomenon, like desire paths.

Group by association

A few months after making the original categorical list and ignoring it, I added a handful of books in a new superlist. It sits at the same super-level as "Fiction" and "Nonfiction".

- Tech Bro canon, the rationalist world

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

- Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies

- Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Gang Leader for A Day by Sudhir Venkatesh

- Andy Weir: the Egg

- Finite and Infinite Games

- Zero to One

- Beginning of Infinity

It's not well grouped by genre. There's mostly nonfiction here, but of different types, and there's even some fiction.

It's more of a gesturing vaguely at something grouping than a legible or describable one. That's what makes these lists useful! They are easier to recall because they more closely match your thoughts, which gesture vaguely at the illegible.

Associative lists are good for collection, because they are easy to create. Each associative list is independent of each other. One list might point at "the melancholy of the big city" and include an Elliott Smith song, another might point to "a cozy high" and include the same Elliott Smith song. You do not have to search through existing lists to create a new one, like with categorical groupings, because the same song can be in multiple groups.

Lists are useful, actually

Lists assist collection and recall. They are especially important tools to deal with excessive amounts of information, which in the Information Age is basically everything. The structure of your lists, therefore, dictates what you know.

People can only do what they remember. Human minds are not default systematic, and the extent to which they are systematic is constrained by what they recall. Associative lists structure your collections more like your thoughts, and in my experience are more useful.

A lot of fields of study, too, are defined by listmaking. What is history if not grouping individual people and events into some useful structure?

Most scholars group history by category: movements and eras and trends. This is the most logically consistent. But what would an associative history look like?

What would history look like if it was less like Wikipedia and more like Spotify playlists?